When a patient walks into your office with a prescription for a brand-name drug, you know the cost. You also know the history: years of clinical trials, marketing campaigns, and patent protections. But when you switch that prescription to a generic, do you really know what you’re getting? For decades, providers have questioned whether generics deliver the same results. The answer isn’t opinion-it’s in the data.

Generics aren’t just cheaper-they’re clinically equivalent

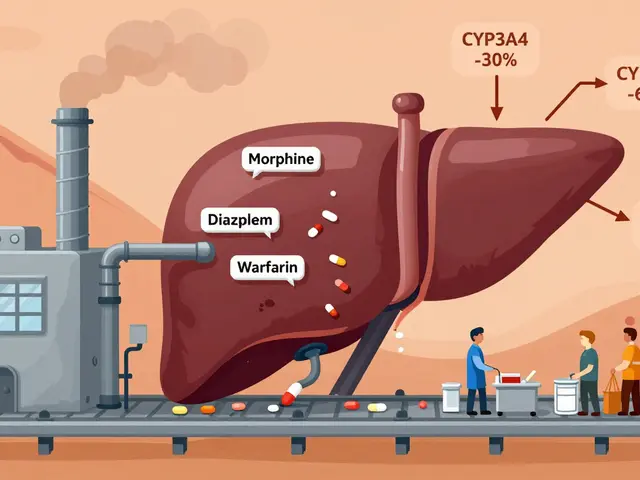

The FDA doesn’t approve a generic drug because it’s inexpensive. It approves it because it works the same. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, generic manufacturers must prove bioequivalence: their product must deliver the same active ingredient, in the same amount, at the same rate as the brand-name version. That means the concentration of the drug in the bloodstream-measured by AUC and Cmax-must fall within 80% to 125% of the brand’s levels. For most drugs, that’s a tight range. For narrow therapeutic index drugs like warfarin or levothyroxine, the standards are even stricter, using scaled bioequivalence methods that account for individual patient variability. The numbers don’t lie. In 2022, generics made up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. Yet they accounted for just 23% of total drug spending. That’s not a fluke. It’s the result of rigorous science. A 2019 study in PLOS Medicine looked at over 1.3 million patients across 14 clinical endpoints-heart attacks, hospitalizations, diabetes control, depression relapse-and found no meaningful difference in outcomes between generics and brand-name drugs in 12 of those 14 cases. For amlodipine, the generic version actually showed slightly better cardiovascular outcomes. For glipizide, insulin initiation rates were identical. For alendronate, fracture rates were the same.What about psychiatric meds? The exceptions that prove the rule

The most common concern among providers isn’t about heart drugs or blood pressure meds. It’s about antidepressants. Studies show slightly higher psychiatric hospitalization rates with generics for escitalopram and sertraline. But here’s what those numbers don’t tell you: the same pattern appeared when researchers compared authorized generics-identical to the brand, just sold under a different label-to the original brand-name drug. That’s critical. If the drug is chemically identical, and outcomes still differ, the issue isn’t the medication. It’s perception. Patients expect brand-name drugs to work better. That expectation can trigger nocebo effects: negative outcomes caused by belief, not biology. One study found patients who switched from brand to generic were more likely to report side effects-even when the drug was the exact same chemical compound. The FDA’s own switch-back analysis showed patients rarely returned to brand-name drugs after starting a generic, unless they were told the switch was happening. When providers didn’t mention it, adherence stayed the same.The real risk isn’t the drug-it’s the confusion

You might think the biggest problem with generics is efficacy. It’s not. It’s inconsistency in labeling and appearance. Generic pills can look completely different from the brand. Different color. Different shape. Different imprint. For patients, especially older adults or those on multiple medications, that’s disorienting. One study found nearly 40% of patients believed a pill that looked different was less effective-even if it was the exact same generic they’d taken before. That’s why education matters. You don’t need to be a pharmacologist to explain this: generic drugs must meet the same FDA standards as brand-name drugs. They’re held to the same manufacturing quality rules. They’re tested on the same bioequivalence benchmarks. The only difference? The price. The FDA’s own adverse event database shows generic drugs are involved in just 0.02% of all reported adverse events, compared to 3.2% for brand-name drugs. That’s not a flaw in generics-it’s proof they’re safer because they’re used more widely, with better monitoring.

Therapeutic equivalence ratings: What the Orange Book really means

The FDA’s Orange Book is your go-to tool for sorting out which generics are truly interchangeable. Most generics-97%-are rated as “A.” That means they’re therapeutically equivalent. You can switch them freely. The other 3% are “B.” Those are the tricky ones: complex formulations like inhalers, topical creams, or certain extended-release tablets where bioequivalence is harder to prove. For those, you need to dig deeper. Look at the specific product. Check if it’s been studied in real-world populations. For example, a generic inhaler might meet bioequivalence standards in healthy volunteers but behave differently in someone with severe COPD. That’s why the FDA’s 2023 draft guidance on complex generics emphasizes real-world evidence over lab-based testing. If you’re prescribing one of these, don’t assume. Ask: Has this been tested in the patient population I’m treating?What the data says about long-term outcomes

A 2020 study tracking 3.5 million Medicare beneficiaries over five years found something surprising: patients on generics had higher survival rates than those on brand-name drugs. At first glance, that sounds like generics are better. But when researchers adjusted for patient health-using statistical methods that account for who gets prescribed what-the gap vanished. The real story? Healthier patients, with better access and more consistent care, were more likely to get generics. That’s not because generics are stronger. It’s because the system favors them for cost reasons. That’s why population-level data is so powerful. Individual anecdotes matter, but they don’t drive policy. The Congressional Budget Office estimates generics saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.68 trillion between 2008 and 2017. In 2021 alone, they saved $377 billion. That’s not just money. It’s access. It’s patients who can afford their meds. It’s fewer skipped doses. It’s lower hospitalization rates from uncontrolled chronic disease.

What you should do next

You don’t need to be convinced. The data is already in. But you do need to act on it.- Start by prescribing generics by default-unless there’s a clear, documented reason not to.

- When switching a patient, explain why. Say: “This generic has the same active ingredient and works the same way. It’s been tested just as rigorously.”

- Use the Orange Book. If it’s rated “A,” you can switch confidently.

- Watch for patients who report new side effects after a switch. Don’t assume it’s the drug. Ask if they noticed the change in appearance. Often, it’s anxiety, not pharmacology.

- Track outcomes in your own practice. Do patients on generics have worse HbA1c? Higher blood pressure? If not, you’ve got real-world proof.

Why this matters beyond the prescription pad

Prescribing generics isn’t just about cost. It’s about equity. A patient who can’t afford their brand-name statin might skip doses. Or stop entirely. That’s when strokes happen. That’s when hospitalizations rise. Generics keep people on treatment. They reduce disparities. They make chronic disease management possible for people who aren’t wealthy. The evidence is clear: for nearly every drug, every condition, every patient population, generics deliver the same clinical outcomes. The only thing they’re missing is the brand name. And that’s not a weakness. It’s the point.Are generic drugs as safe as brand-name drugs?

Yes. Generic drugs are held to the same FDA manufacturing and quality standards as brand-name drugs. The FDA reviews every generic for safety, potency, and consistency. Adverse event reports show generics are involved in far fewer incidents than brand-name drugs-0.02% versus 3.2%-because they’re used more widely and monitored more closely.

Do generics take longer to work than brand-name drugs?

No. Bioequivalence testing requires generics to reach the same blood concentration levels as the brand-name drug at the same rate. If a brand-name drug works in 30 minutes, the generic must too. Any perceived delay is usually due to patient expectations, not pharmacology.

Can I switch a patient from brand to generic safely?

For 97% of drugs, yes. If the generic is rated “A” in the FDA’s Orange Book, it’s considered therapeutically equivalent. For narrow therapeutic index drugs like levothyroxine or warfarin, monitor closely after the switch-but most patients transition without issue. The key is communication: tell the patient you’re switching, and why.

Why do some patients say generics don’t work for them?

Often, it’s not the drug-it’s the change. Generic pills look different. Patients associate appearance with effectiveness. Studies show patients report more side effects after switching to generics-even when the drug is chemically identical. This is a psychological effect, not a pharmacological one. Address it with clear, simple education.

Are authorized generics better than regular generics?

Authorized generics are made by the brand-name company and are chemically identical. They’re often preferred by patients who are skeptical of generics, and switching back to brand is less common with them. But clinically, they’re no different from other FDA-approved generics. Both meet the same standards. The choice is about patient comfort, not clinical superiority.

Should I avoid generics for chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension?

No. Large studies of metformin, amlodipine, and lisinopril show identical control of HbA1c, blood pressure, and cardiovascular events between generics and brands. In fact, generics improve adherence because they’re affordable. For chronic conditions, cost is the biggest barrier to adherence-and generics remove it.

Vicki Yuan

Finally, someone laid out the data without fluff. I’ve been prescribing generics for years, but I still get pushback from patients who think the blue pill is ‘weaker’ than the red one. The FDA’s bioequivalence standards are rock-solid-97% of generics are A-rated, and the science backs it. No more excuses.

Uzoamaka Nwankpa

It’s not about the science. It’s about trust. When your patient sees a pill that looks nothing like what they’ve taken for 10 years, they don’t care about AUC or Cmax. They care that it doesn’t look right. And you know what? That’s valid.

Chris Cantey

One must ask: if generics are so identical, why does the pharmaceutical industry spend billions marketing the brand? Is it not the placebo effect, writ large, that sustains the myth of superiority? The system profits from perception, not pharmacology. We are not merely prescribing drugs-we are perpetuating a cultural ritual of brand worship.

Abhishek Mondal

Let’s be precise: bioequivalence is defined as 80–125% AUC and Cmax-yes, but that’s a 45% window! That’s not ‘identical’-it’s statistically tolerable. And for narrow-therapeutic-index drugs? Even then, inter-patient variability can push a patient into subtherapeutic or toxic ranges. You’re oversimplifying. Real-world pharmacokinetics isn’t a lab equation.

Oluwapelumi Yakubu

Man, this is the kind of truth-telling we need! You see, in Nigeria, we don’t even have access to generics half the time-so when we do, we treat ‘em like gold. But here’s the thing: if a man can afford a $200 brand-name pill, he’s probably got better care overall. The real villain isn’t the generic-it’s the system that makes people choose between rent and refills. Generics? They’re the unsung heroes.

melissa cucic

While the data is compelling, and the FDA’s standards are rigorous, we must acknowledge the psychological dimension of medication adherence. The patient’s perception of efficacy is, in many cases, as clinically significant as the pharmacokinetic profile. The nocebo effect is not trivial; it is measurable, reproducible, and ethically relevant. Education must be systemic-not just a handout at the pharmacy.

en Max

It is imperative to recognize that the clinical equivalence of generics is not merely a regulatory construct-it is an empirically validated phenomenon across multiple longitudinal cohort studies, meta-analyses, and real-world observational databases. The 2019 PLOS Medicine study, with its 1.3 million patient sample, represents one of the most robust confirmations of therapeutic parity in modern pharmacoeconomics. Furthermore, the 0.02% adverse event rate for generics, when normalized against utilization volume, demonstrates superior safety surveillance and distribution integrity.

Angie Rehe

Stop pretending this is just about science. You’re ignoring the fact that 30% of patients report ‘worse results’ after switching-and you’re calling it a nocebo? That’s medical gaslighting. If the patient says it doesn’t work, you listen. You don’t lecture them about bioequivalence. You change the pill back. End of story.

Jacob Milano

I love how you broke this down. I had a patient last week who swore her generic lisinopril made her dizzy-turned out she’d switched from the green capsule to a white one and thought it was a different drug. We sat down, showed her the FDA page, and she cried. Not from side effects-from relief. That’s the real win here: clarity.

Enrique González

Generics saved my dad’s life. He’s on warfarin. Switched from Coumadin to generic. Same dose. Same INR. Same results. But now he can afford his blood tests. That’s not just science-that’s dignity.

saurabh singh

Bro, in India we’ve been using generics since the 80s-before it was cool. My uncle took generic metformin for 20 years, no issues. But here’s the kicker: the Indian generics are often better made than the brand ones in the US. Quality control isn’t about where it’s made-it’s about who’s watching. And yeah, the Orange Book? Use it. It’s your bible.

Siobhan Goggin

My mum switched to generic sertraline and said she felt ‘numb’. We went back to brand. She’s fine now. I know the data says it’s the same-but I’m not gonna risk her mental health on a pill that looks like a Skittle.

Ashley Viñas

Let’s be honest: if you’re prescribing generics because you’re too lazy to look up the Orange Book, you’re not being cost-conscious-you’re being negligent. And if you’re dismissing patient concerns as ‘nocebo’ without even checking the pill’s appearance or the manufacturer’s reputation? You’re not a provider-you’re a bureaucrat in a white coat.