When your liver isn’t working right, even normal doses of common medications can become dangerous. This isn’t theoretical-it’s happening every day to millions of people with liver disease. The liver doesn’t just filter toxins; it’s the main factory for breaking down drugs. When liver function drops, that factory slows down, and drugs build up in the body. The result? Overdose effects from pills that were meant to be safe. This is especially true for people with cirrhosis, hepatitis, or advanced fatty liver disease. And the problem is getting worse. With over 22.5 million Americans living with chronic liver disease, understanding how drugs are cleared-or not cleared-has become a critical part of safe prescribing.

How Liver Disease Slows Down Drug Clearance

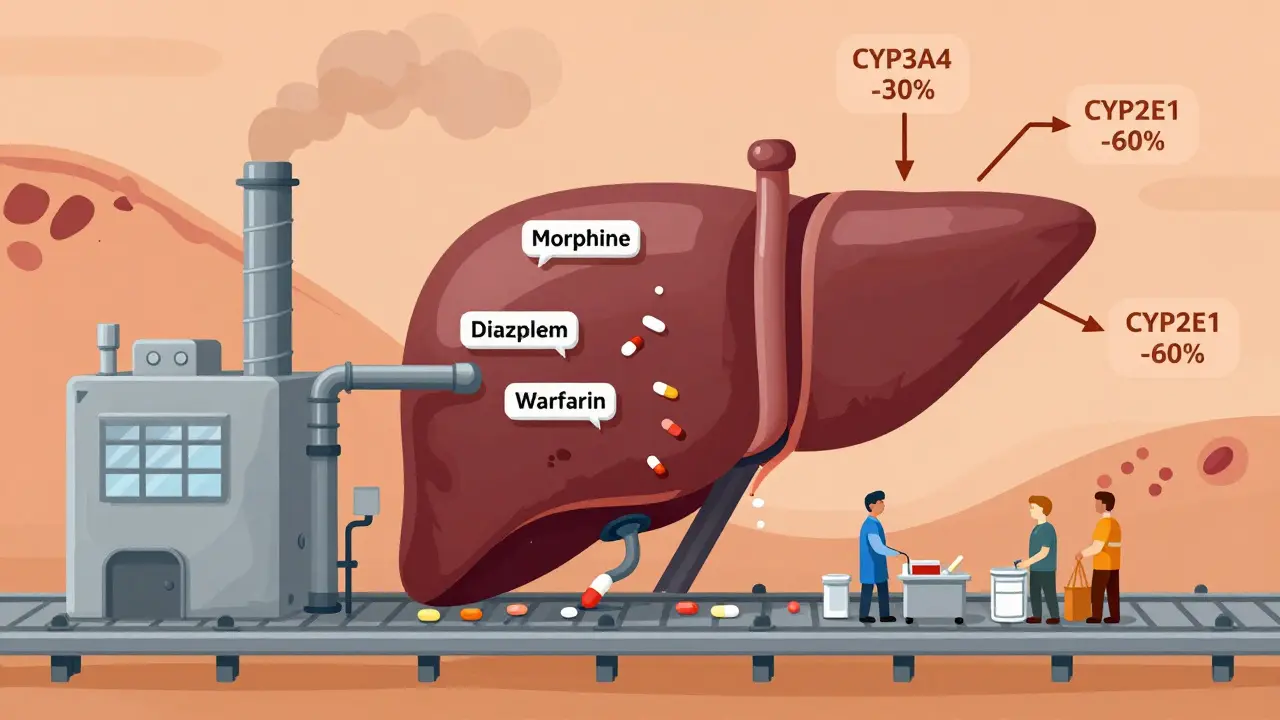

The liver clears drugs in three main ways: metabolism by enzymes, direct excretion into bile, and filtering through blood flow. Liver disease messes with all three. In cirrhosis, healthy liver tissue is replaced by scar tissue. Blood flow drops because vessels get blocked and shunted. The number of working liver cells falls by 30-50%. And the enzymes that break down drugs? They’re turned down, sometimes by half.

Two key enzyme families take the biggest hit: CYP3A4 and a major liver enzyme responsible for metabolizing more than 50% of all prescription drugs, and CYP2E1 and a key enzyme for processing alcohol, acetaminophen, and some anesthetics. In advanced cirrhosis, CYP3A4 activity drops 30-50%. CYP2E1? It can fall by as much as 60%. That means drugs like statins, antidepressants, and opioids stick around much longer than they should.

Transporters matter too. Proteins like OATP1B1 and a liver transporter that pulls drugs like statins and methotrexate into liver cells for processing become less active. When OATP1B1 drops by 50-70%, drugs can’t even get into the liver to be broken down. They just sit in the bloodstream, increasing the risk of side effects.

High-Extraction vs. Low-Extraction Drugs: What’s the Difference?

Not all drugs are affected the same way. The liver handles two broad categories: high-extraction and low-extraction drugs.

High-extraction drugs (like fentanyl, morphine, and propranolol) rely on blood flow. If liver blood flow drops from 1.5 L/min to 0.8 L/min-as it does in cirrhosis-clearance drops sharply. These drugs are cleared fast in healthy people, but in liver disease, they don’t get filtered at all. That’s why morphine can cause dangerous sedation in cirrhotic patients even at low doses.

Low-extraction drugs (like diazepam, lorazepam, and methadone) depend on enzyme activity. These make up about 70% of all commonly prescribed drugs. Even small drops in enzyme function cause big changes in how long they last. A 40% drop in CYP3A4 can double the half-life of a drug like midazolam. That’s why a single dose of a benzodiazepine can leave a cirrhotic patient confused or unresponsive for hours.

Real-World Drug Examples and Dose Adjustments

Here’s what this looks like in practice:

- Warfarin: Clearance drops 30-50% in cirrhosis. Dose reductions of 25-40% are often needed to avoid dangerous bleeding. A standard 5 mg dose can push INR levels into the danger zone.

- Diazepam: Has active metabolites that stick around for days. In cirrhosis, dose reductions of 50-70% are recommended. Even 2 mg can cause prolonged sedation.

- Lorazepam: No active metabolites. Clearance is less affected. A 25-40% dose reduction is usually enough. It’s often the safer choice in liver disease.

- Ceftriaxone: A common antibiotic. In cirrhosis, peak blood levels can rise 40-60% because the liver can’t clear it. This increases the risk of side effects like diarrhea and allergic reactions.

- Direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) for hepatitis C: In Child-Pugh C cirrhosis, improper dosing led to 22.7% treatment failure rates. Correct dosing cut that to 5.3%.

Some drugs are safer. Sugammadex and a neuromuscular blocker that’s 96% cleared by the kidneys doesn’t need dose changes in mild-to-moderate liver disease. But even here, recovery time is 40% longer. That’s a clue: if a drug is mostly cleared by the kidneys, the liver still plays a backup role.

How Doctors Measure Liver Function-And Why It Matters

Lab tests alone don’t tell the whole story. A normal ALT or AST doesn’t mean the liver is working fine. The key is functional capacity-not just inflammation.

The Child-Pugh score and a clinical tool that uses bilirubin, albumin, INR, ascites, and encephalopathy to classify liver disease severity into Class A, B, or C is the gold standard. Class C means severe impairment: bilirubin >3.0 mg/dL, albumin <2.8 g/dL, INR >2.3. Dose reductions are steep here: 50-75% for high-extraction drugs.

The MELD score and a score based on bilirubin, INR, and creatinine that predicts survival in liver disease is also useful. For every 5-point increase above MELD 10, drug clearance drops about 15%. So a patient with MELD 20 has 30% less clearance than someone with MELD 10.

But here’s the catch: drug levels don’t always match these scores. Two patients with the same Child-Pugh B score can have wildly different drug responses. That’s why therapeutic drug monitoring-measuring actual blood levels-is essential for drugs with narrow safety margins, like warfarin, tacrolimus, or phenytoin.

What’s Changing in Drug Development and Guidelines

The industry is waking up. In 2023, the FDA approved 18 new drugs with specific liver disease dosing instructions-a 25% jump from 2022. The EMA now requires hepatic impairment studies for every new drug. Over 90% of new drug applications include these studies now, up from 65% in 2018.

Pharmacists are stepping in too. Between 2020 and 2023, pharmacist-led dose adjustment services for liver patients rose 40%. Hospitals are now using physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models and computer simulations that predict drug behavior based on liver blood flow, enzyme levels, and shunting to guide dosing. These models are 85-90% accurate in predicting how a drug will behave in cirrhosis.

And it’s not just cirrhosis anymore. MASLD and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, formerly called NAFLD, affecting 30% of U.S. adults can reduce CYP3A4 activity by 15-25% even before scarring shows up on a scan. That means even early fatty liver can change how drugs work. This is a hidden risk most doctors still miss.

What Patients and Providers Need to Do

- Always tell your doctor if you have liver disease-even if you’re told it’s "mild."

- Ask: "Is this drug cleared by the liver? Do I need a lower dose?"

- Watch for signs of drug buildup: drowsiness, confusion, dizziness, nausea, or unexplained bruising.

- For high-risk drugs (opioids, benzodiazepines, anticoagulants), request blood level monitoring if possible.

- Use tools like the Child-Pugh or MELD score when available-they’re more reliable than liver enzyme tests alone.

The bottom line: Liver disease doesn’t just affect the liver. It changes how every drug works in your body. What’s safe for one person can be dangerous for another. The old rule of thumb-"one size fits all"-doesn’t work anymore. Precision dosing isn’t the future. It’s the present.

Can liver disease cause drug overdose even at normal doses?

Yes. In cirrhosis or advanced liver disease, the liver’s ability to break down drugs can drop by 30-70%. This means drugs like opioids, benzodiazepines, and statins build up in the bloodstream. A standard dose can become an overdose, leading to sedation, confusion, or even coma. This is why dose reductions are often required.

Are there drugs that are safe to use in liver disease?

Yes. Drugs that are cleared mostly by the kidneys-like sugammadex, gabapentin, or ceftriaxone-don’t need major dose changes in mild-to-moderate liver disease. But even these can have altered effects. Drugs with wide safety margins, like acetaminophen (at low doses), are often safer than others. Still, all medications should be reviewed individually.

Why do some patients with cirrhosis react worse to sedatives?

The liver doesn’t just metabolize sedatives-it also helps clear toxins like ammonia. In cirrhosis, ammonia builds up and makes the brain more sensitive to sedatives. Even normal blood levels of a drug like midazolam can cause deep sedation or hepatic encephalopathy. This is why doctors often choose lorazepam over diazepam-it’s less likely to cause confusion.

Is a normal liver enzyme test enough to say a drug is safe?

No. Liver enzymes like ALT and AST measure inflammation, not function. A patient can have normal enzymes but severe scarring and reduced drug clearance. The Child-Pugh score and MELD score are better indicators of how well the liver is working as a drug-processing organ.

How can I know if my medication dose needs adjusting?

Talk to your pharmacist or prescriber. Ask if your drug is metabolized by the liver, what its clearance pathway is, and whether liver disease affects its dosing. If you’re on a drug with a narrow therapeutic window-like warfarin, digoxin, or tacrolimus-ask about therapeutic drug monitoring. Blood tests can confirm if levels are too high.