Getting insulin dosing wrong isn’t just a mistake-it can land you in the hospital. One extra unit, the wrong syringe, or a miscalculated carb ratio can send blood sugar crashing. And it happens more often than you think. In the U.S., about 7.4 million people use insulin daily. For many, the biggest danger isn’t the disease-it’s the dose.

Understanding Insulin Concentrations: U-100 vs. U-500

Not all insulin is the same. Most people use U-100 insulin-that’s 100 units per milliliter. It’s the standard. But some people with severe insulin resistance need U-500, which is five times stronger. If you use a U-100 syringe to draw up U-500 insulin, you’re giving yourself five times the dose you think you are. That’s not a typo. That’s a medical emergency.U-100 insulin contains about 34.7 micrograms of insulin per unit. U-500? Each unit is roughly 36 micrograms, but because it’s packed five times denser, you need a special syringe labeled for U-500. Mixing them up isn’t just risky-it’s deadly. Always check the vial label. If it says U-500, don’t use a regular syringe. If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist. There’s no room for guesswork.

The Syringe That Could Save Your Life

Insulin syringes aren’t all the same. They come in three sizes: 0.3 mL, 0.5 mL, and 1 mL. Each is marked for U-100 insulin. A 0.3 mL syringe holds up to 30 units. A 1 mL holds 100. If you’re taking 25 units, use the 0.3 mL or 0.5 mL syringe. Why? Because it’s easier to read. A 1 mL syringe for a 25-unit dose means you’re guessing between lines. More room for error.Always match the syringe to your dose. Never use a syringe meant for another type of medication. Insulin syringes have thin needles and are calibrated in units, not milliliters. Using a regular TB syringe (meant for vaccines or antibiotics) can lead to massive overdoses. One study found that nearly 20% of insulin errors involved the wrong syringe. Don’t be part of that statistic.

How Hypoglycemia Happens-And How to Stop It

Hypoglycemia-low blood sugar-is the most common and dangerous side effect of insulin. It can strike fast. Sweating, shaking, confusion, dizziness, even seizures. Your brain needs glucose. When insulin drops it too low, things go south fast.Most hypoglycemic episodes happen because of mismatched insulin and food. You took your usual 8 units for breakfast, but you skipped the toast. You exercised after your shot. You switched from one insulin to another without adjusting the dose. All of these are classic triggers.

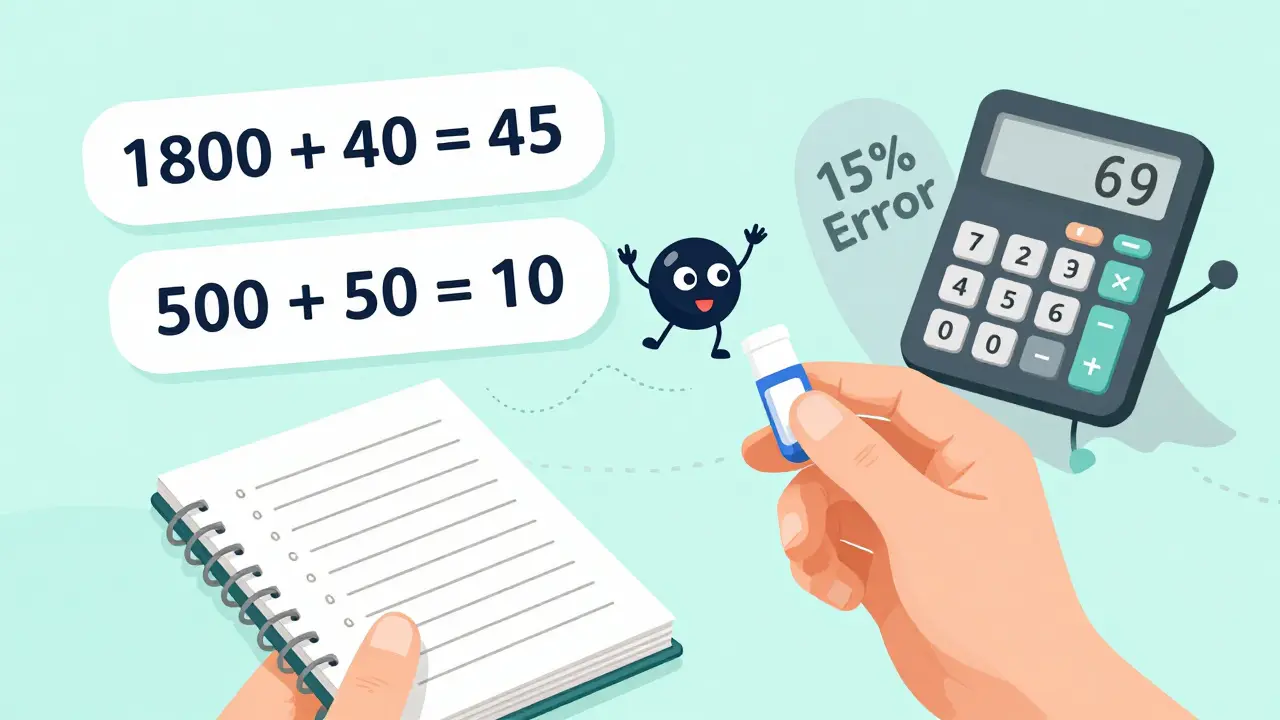

Use the Rule of 1800 to calculate your correction factor. Take 1800 and divide it by your total daily insulin dose. If you take 40 units a day, 1800 ÷ 40 = 45. That means one unit of rapid-acting insulin lowers your blood sugar by about 45 mg/dL. So if your reading is 220 and your target is 100, you need about 2.7 units to correct it. Round to 3 units. Don’t overcorrect. And always carry fast-acting sugar-glucose tabs, juice, or candy. Never rely on a snack alone. You need pure glucose to act fast.

Carb Counting and the 500 Rule

How much insulin do you need for your meal? The 500 Rule helps. Divide 500 by your total daily insulin dose. If you take 50 units a day, 500 ÷ 50 = 10. That means one unit of insulin covers about 10 grams of carbs.So if you’re eating a sandwich with 60 grams of carbs, you’d need 6 units. But here’s the catch: this number isn’t set in stone. Some people need 1 unit for every 6 grams. Others can stretch it to 20. It depends on your sensitivity, activity level, and even stress. That’s why you track your results. Did your blood sugar spike after eating 50 grams with 5 units? Adjust. Did it drop too low after 3 units for 30 grams? Cut back.

Don’t guess. Write it down. Use an app or a notebook. Over time, you’ll see patterns. Your carb ratio might change in the morning versus dinner. That’s normal. Your body isn’t a machine. It’s a living system. Learn its rhythm.

Switching Insulins? Don’t Guess the Dose

Switching from NPH to Lantus? From Tresiba to Basaglar? You can’t just swap them 1:1. That’s where most errors happen.When switching from NPH to a long-acting analog like Lantus or Basaglar, reduce your dose by 20%. So if you were on 60 units of NPH, start with 48 units of Lantus. Why? NPH has a peak effect. Analogs don’t. You’re less likely to have a low in the middle of the night, but you also get less total coverage. Cut back to avoid stacking.

Switching from Tresiba (once daily) to Basaglar (twice daily)? Divide your daily dose by two. If you take 100 units of Tresiba, you’ll start with 50 units of Basaglar twice a day. But some experts suggest using only 80% of your original dose-so 40 units twice. Always follow your provider’s guidance. Never assume.

When you switch, check your blood sugar more often-for at least two weeks. Your body is adjusting. Your insulin timing, absorption, and sensitivity are all shifting. Don’t wait for a low to happen. Be proactive.

Titration: Small Changes, Big Results

You don’t need to change your insulin dose by 10 units at once. That’s how people end up in the ER. Adjust slowly.For fasting blood sugar:

- If it’s < 60 mg/dL → reduce your basal dose by 4 units or more

- If it’s 60-99 mg/dL → reduce by 2 units

- If it’s 100-139 mg/dL → no change

- If it’s 140-159 mg/dL → increase by 2 units

- If it’s 160-179 mg/dL → increase by 4 units

- If it’s ≥180 mg/dL → increase by 6-8 units

Wait 3-4 days after each change before adjusting again. Your body needs time to respond. Don’t tweak every day. That leads to wild swings. Keep a log. Note your dose, your food, your activity, and your readings. Patterns will show up.

Why the Wrong Conversion Factor Is a Silent Killer

Here’s something most people don’t know: the way insulin is measured in labs and online calculators is often wrong. Insulin is measured in units (IU or U), not milligrams. But some systems use a conversion factor of 6.0 to turn units into mass (pmol/L). The correct factor is 5.18.That 15% error? It’s hiding in lab reports, apps, and even some medical textbooks. If your doctor or app uses the wrong number, your dose might be off by 15%. That’s the difference between 10 units and 11.5 units. For someone on 50 units a day, that’s 7.5 extra units. Enough to cause a severe low.

Ask your lab or pharmacy: “Do you use the correct insulin conversion factor of 5.18?” If they don’t know what you mean, it’s time to double-check your calculations manually. Don’t trust automated tools blindly. Verify the math. Your life depends on it.

When to Call for Help

You’re not alone in this. But you shouldn’t have to figure it out alone. Call your provider if:- You’ve had two or more unexplained lows in a week

- Your blood sugar stays above 250 mg/dL for more than two days

- You’re confused, dizzy, or can’t think clearly after a low

- You’re switching insulins and don’t know how to adjust

- You’re unsure which syringe to use

There’s no shame in asking. Insulin is powerful. It’s not like a painkiller. One wrong step can change everything. Get help before it’s an emergency.

Final Reminder: Safety Is a Habit

Insulin safety isn’t about memorizing rules. It’s about building habits:- Always check the vial label before drawing up

- Use the right syringe for your dose and insulin type

- Calculate your correction and carb ratios using the 1800 and 500 rules-but adjust based on your body

- Never switch insulins without a plan from your care team

- Keep glucose tabs with you, always

- Log your doses and readings daily

- Question any number that feels off-even if it’s on a screen

Diabetes doesn’t care how smart you are. It only cares how careful you are. The best dose is the one you get right-every single time.

Jenci Spradlin

just got my new insulin pens and i swear i almost used the wrong one-thank god i double-checked the label. u-500 looks like u-100 if you’re tired. never skip the label check. i’m still shaking thinking about it.

RAJAT KD

This post is dangerously incomplete. You didn’t mention that U-500 syringes are color-coded red in the U.S. and blue in Europe. Mixing them up is not just a mistake-it’s a death sentence. And no, your pharmacy won’t always tell you. You have to demand it.

Micheal Murdoch

Insulin isn’t just medicine-it’s a daily negotiation with your body. The 500 and 1800 rules are starting points, not gospel. I’ve been on insulin for 18 years. My carb ratio changes in winter. My correction factor shifts when I’m stressed. I track everything. Not because I’m obsessive-because my pancreas quit and my brain has to do its job now. You’re not a machine. Your insulin shouldn’t treat you like one.

Write it down. Even if it’s scribbled on a napkin. Patterns emerge. And when they do, you stop guessing. You start knowing.

And yes-always carry glucose tabs. Not candy. Not juice. Glucose tabs. They hit fast. Everything else is a delay you can’t afford.

tali murah

Oh wow. A comprehensive guide on not killing yourself with insulin. How novel. I suppose next you’ll warn us not to stick our fingers in electric sockets. Truly, groundbreaking stuff. I’m sure everyone who’s lived with diabetes for more than three minutes didn’t already know this. Maybe you should write a pamphlet for toddlers too.

Jeffrey Hu

Actually, the 1800 rule is outdated. Most endocrinologists now use 1500 for rapid-acting analogs because of their faster onset. And the 500 rule? That assumes a 24-hour cycle, but if you’re on a 16-hour eating window, your ratio changes. Also, the conversion factor isn’t 5.18-it’s 6.009 for insulin glargine in some EU labs. You’re spreading misinformation. Don’t trust random internet posts.

Matthew Maxwell

People like you make me sick. You write a 2000-word guide and think you’ve saved lives, but you didn’t. You just gave false confidence. The real problem? Doctors who don’t explain this. Pharmacies that don’t train staff. Insurance companies that won’t cover U-500 syringes. You’re blaming the patient for not being perfect while the system is rigged. Shame on you for not saying that.

Jacob Paterson

So let me get this straight-you think writing a wall of text about insulin syringes makes you a hero? Meanwhile, people in rural areas can’t even get U-500 insulin without a 3-week wait. You’re preaching to the choir who already knows this. What about the people who can’t afford the right syringes? Or the ones whose doctors still prescribe NPH and don’t know the difference? Your ‘safety habits’ are a luxury. Real people are dying because of bureaucracy, not because they forgot to check a label.

Johanna Baxter

I cried reading this. Not because it’s perfect-but because someone finally said it. I had a seizure last year because I used a TB syringe. I thought ‘it’s just a needle, right?’ No. It’s not. I’m alive because my roommate saw me shaking and gave me juice. I didn’t have tabs. I thought candy would do. It didn’t. Please. Just… carry tabs. Always.

Aron Veldhuizen

Actually, the 500 Rule is statistically invalid for patients with insulin resistance. The formula assumes linear pharmacokinetics, which is false for U-500 users. The real ratio is nonlinear and requires population pharmacokinetic modeling-which no app or calculator does. You’re promoting pseudoscience under the guise of safety. Also, glucose tabs are useless if you’re unconscious. Glucagon is the only real solution. Why didn’t you mention that?

Patty Walters

thank u for this. i’ve been using the same syringe for 2 years bc i thought they were all the same. i just switched to the 0.5ml ones for my 30u doses. it’s so much easier to read. i feel dumb for not knowing sooner. but now i do. and i’m not gonna forget.

Gregory Clayton

Man, I just got back from the VA and they gave me a U-100 syringe for my U-500. I said ‘are you serious?’ and they laughed. I’m not kidding. This isn’t just about carelessness-it’s about negligence. We’re veterans. We don’t need to be killed by bureaucracy. Someone needs to get fired.

Catherine Scutt

Wow. You wrote all this and still didn’t mention that insulin expires after 28 days open. Or that heat ruins it. Or that storing it in your car in Arizona is basically a suicide note. You’re missing the basics. If you’re this careless with the fundamentals, why should we trust your advanced advice?

Jerian Lewis

I used to think I was careful. Then I accidentally gave my kid 10 units instead of 1 because I misread the syringe. He was fine. But I haven’t slept since. I now label every vial with a Sharpie. I use a magnifying glass. I triple-check. I don’t care how weird it looks. I’d rather be the weird one than the dead one.

Kiruthiga Udayakumar

From India: We don’t even have U-500 insulin in most cities. People use U-100 in double doses. No one knows the difference. This post should be translated. And distributed. Not just to Reddit. To clinics. To pharmacies. To schools. This is a public health crisis here too.