Vasculitis is not one disease-it’s a group of rare autoimmune conditions where the body’s own immune system attacks its blood vessels. This inflammation can narrow, weaken, or block vessels, cutting off blood flow to organs and tissues. Without treatment, it can lead to serious damage in the kidneys, lungs, nerves, skin, or even the brain. The good news? Most forms are treatable, especially when caught early. The challenge? Symptoms often look like the flu, a cold, or arthritis, which means many people wait months before getting the right diagnosis.

How Vasculitis Starts: When the Immune System Turns Against You

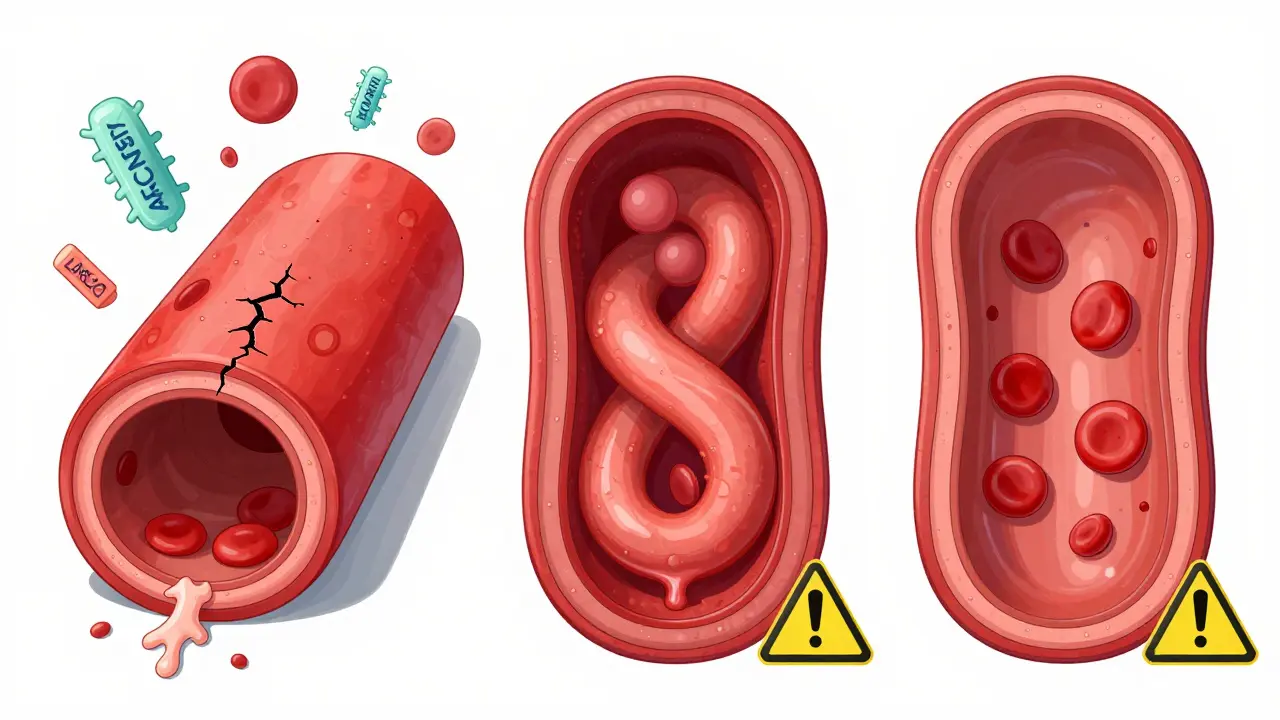

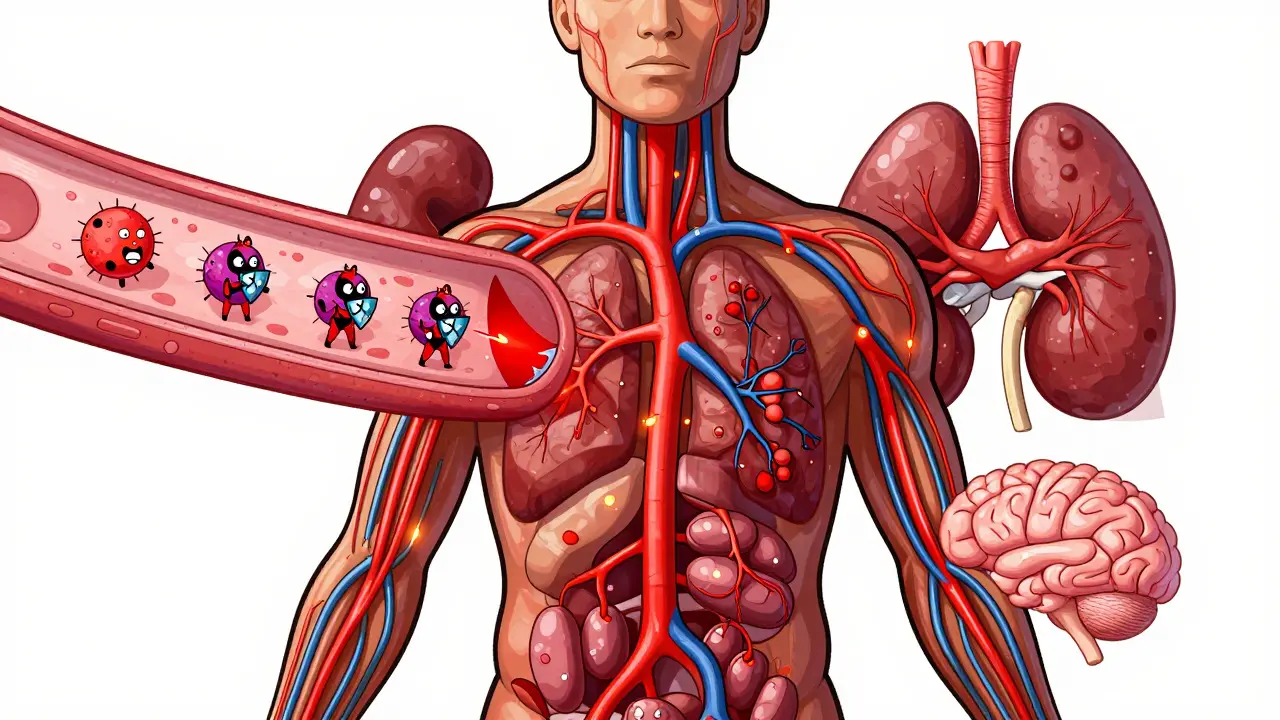

Your immune system is designed to protect you-from viruses, bacteria, and other invaders. But in vasculitis, something goes wrong. It starts mistaking the walls of your blood vessels as foreign. In response, white blood cells swarm the area, causing inflammation. This isn’t just swelling. It’s destruction. The vessel wall thickens, loses elasticity, and may develop holes or bulges called aneurysms. In severe cases, the vessel closes completely, starving nearby tissue of oxygen.This process can happen in vessels of any size-from the large aorta down to the tiniest capillaries. That’s why symptoms vary so much. One person might have a rash on their legs; another might struggle to breathe because their lung arteries are inflamed. The same immune attack can affect multiple organs at once, making it hard to pin down.

Types of Vasculitis: Size Matters

Doctors classify vasculitis based on the size of the blood vessels involved. This helps guide diagnosis and treatment.- Large-vessel vasculitis affects the aorta and its major branches. Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is the most common, usually striking people over 50. It often targets the temples, causing headaches, jaw pain when chewing, and sometimes sudden vision loss. Takayasu arteritis is rarer and typically affects younger women, often causing arm pain, weak pulses, and high blood pressure.

- Medium-vessel vasculitis involves arteries like those feeding the intestines, kidneys, or skin. Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) can cause abdominal pain, nerve damage, and kidney failure. Kawasaki disease, which mostly affects children under 5, inflames coronary arteries and can lead to heart problems if not treated quickly.

- Small-vessel vasculitis is the most common group and includes conditions like granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). These often involve the kidneys, lungs, and nerves. Many are linked to ANCA antibodies-autoantibodies that attack white blood cells and trigger vessel inflammation.

Some types, like Behçet’s disease or Buerger’s disease, don’t fit neatly into this system. Behçet’s causes mouth sores, eye inflammation, and genital ulcers. Buerger’s is tied to smoking and affects blood flow in hands and feet, leading to pain and even tissue death.

What Symptoms Should Raise a Red Flag?

There’s no single symptom that screams “vasculitis.” But if you have a mix of these, especially if they come on suddenly and don’t improve with standard treatments, it’s time to see a specialist:- Purple or red spots, bumps, or bruises on the skin that don’t fade with pressure

- Joint pain or muscle aches that feel worse than normal arthritis

- Numbness, tingling, or weakness in hands or feet (nerve damage)

- Shortness of breath or coughing up blood (lung involvement)

- Stomach pain, vomiting, or bloody stools (gut blood vessels affected)

- Headaches, jaw pain, or vision changes (especially if over 50)

- Fever, weight loss, or extreme fatigue without a clear cause

Many patients report feeling like their symptoms were dismissed as “just stress” or “aging.” But vasculitis doesn’t wait. The longer it goes untreated, the more damage it does-especially to the kidneys and lungs.

How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no single blood test for vasculitis. Diagnosis requires piecing together clues:- Blood tests: Elevated ESR and CRP show inflammation. ANCA testing helps identify GPA, MPA, and EGPA. c-ANCA targeting proteinase-3 is 80-90% specific for GPA.

- Urine tests: Even if you feel fine, doctors check for blood or protein in urine-signs of kidney damage, which can happen without symptoms.

- Imaging: CT or MRI scans can show inflamed arteries. A PET scan might reveal active inflammation in large vessels like the aorta.

- Tissue biopsy: This is the gold standard. A small sample of skin, kidney, lung, or nerve tissue is examined under a microscope. Finding immune cells inside the vessel wall confirms vasculitis.

The Five Factor Score is used for polyarteritis nodosa and some other types. It looks at whether you have kidney, heart, gastrointestinal, or nerve involvement to predict how aggressive the disease is and how urgently you need treatment.

Treatment: Stopping the Attack, Restoring Balance

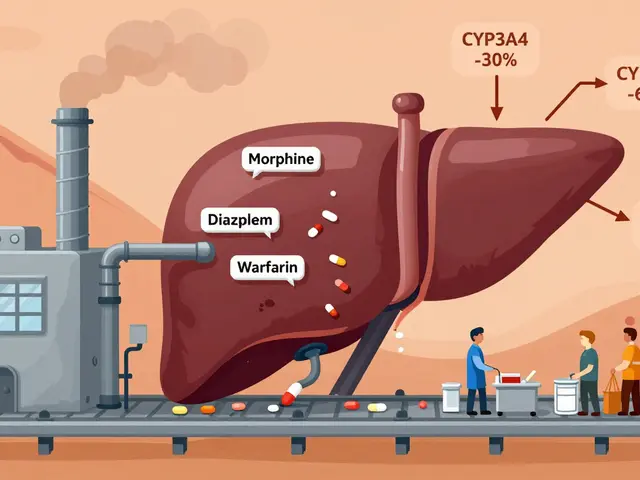

Treatment goals are simple: stop the immune attack fast, protect organs, and keep the disease from coming back.For severe cases, doctors start with high-dose steroids like prednisone-often 0.5 to 1 mg per kilogram of body weight daily. But steroids alone aren’t enough. They cause bone loss, weight gain, diabetes, and mood swings over time. That’s why they’re paired with stronger drugs:

- Cyclophosphamide was the standard for decades, but it carries risks like infertility and bladder cancer.

- Rituximab is now preferred for many ANCA-associated cases. It targets B-cells-the immune cells that make harmful antibodies. It’s just as effective as cyclophosphamide but safer long-term.

- Avacopan, approved in 2021, is a game-changer. It blocks a key part of the immune system (C5a receptor) without suppressing the whole thing. In clinical trials, patients on avacopan cut their steroid dose by 2,000 mg over a year, with fewer side effects.

- Tocilizumab, an IL-6 inhibitor, is now approved as an add-on for giant cell arteritis. It helps patients reduce steroid use and lowers relapse rates.

Once the disease is under control, maintenance therapy begins. This usually lasts 18-24 months and may include methotrexate, azathioprine, or continued rituximab. Stopping too soon increases relapse risk-nearly half of patients with ANCA vasculitis have a flare within five years.

For Buerger’s disease, there’s only one treatment that works: quitting tobacco. No drug, surgery, or therapy will help if you keep smoking.

Prognosis and Long-Term Outlook

With treatment, 80-90% of people with ANCA-associated vasculitis go into remission. But remission doesn’t mean cured. Many live with the risk of flare-ups. Regular blood tests, urine checks, and imaging are lifelong.Survival rates depend on how many organs are affected. The Five Factor Score shows that patients with no major organ damage have a 95% five-year survival rate. If two or more organs are involved, that drops to about 50%. Early diagnosis makes the biggest difference.

Kawasaki disease in children is mostly treatable with IVIG and aspirin, but 20-25% of untreated kids develop coronary artery aneurysms-something that can lead to heart attacks years later. That’s why pediatricians monitor heart function for years after diagnosis.

What’s New in Research?

Scientists are working on better ways to predict flares and personalize treatment:- BAFF and MCP-1 are being studied as biomarkers that could signal an upcoming flare before symptoms appear.

- Mepolizumab, a drug used for severe asthma, is showing promise in EGPA by reducing eosinophil levels that drive inflammation.

- Abatacept, which blocks T-cell activation, is being tested for giant cell arteritis to see if it can replace steroids entirely.

The Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium continues to lead trials that are changing standards of care. The goal? To treat vasculitis with precision-targeting the right immune pathway in the right patient, with fewer side effects.

What Patients Need to Know

If you’ve been diagnosed:- Take your meds exactly as prescribed-even when you feel fine.

- Report new symptoms immediately: numbness, chest pain, blood in urine, or sudden vision changes.

- Get vaccinated. Immunosuppressants increase infection risk. Ask your doctor about flu, pneumonia, and shingles shots.

- Protect your bones. Steroids weaken them. Ask about calcium, vitamin D, and bone density scans.

- Find a rheumatologist who specializes in vasculitis. Generalists often miss it. Specialists know the subtle signs.

Many patients feel isolated. Vasculitis is rare, and few people understand it. Support groups, like those run by the Vasculitis Foundation, can help you connect with others who get it.

Can vasculitis be cured?

There’s no permanent cure for most types of vasculitis, but most people can achieve long-term remission with proper treatment. The goal is to stop the immune attack, protect organs, and prevent flares. Many patients live normal lives with medication and regular monitoring.

Is vasculitis hereditary?

Vasculitis is not directly inherited, but certain genes may make some people more susceptible. Having a family member with an autoimmune disease might slightly increase your risk, but it doesn’t mean you’ll get it. Environmental triggers-like infections or smoking-are usually needed to start the disease.

Can stress cause vasculitis?

Stress doesn’t cause vasculitis, but it can trigger flares in people who already have it. The disease starts from an immune system malfunction, not emotional factors. However, managing stress helps improve overall health and may reduce the frequency of flare-ups.

What happens if vasculitis is left untreated?

Untreated vasculitis can lead to permanent organ damage. Kidneys may fail, lungs can scar, nerves can be destroyed, and aneurysms can rupture. In severe cases, especially when the brain or heart is involved, it can be fatal. Early treatment is the best way to avoid these outcomes.

Are there natural remedies for vasculitis?

No natural remedy can replace medical treatment for vasculitis. Diet, exercise, and supplements might support general health, but they won’t stop the immune system from attacking blood vessels. Relying on alternatives instead of proven drugs can lead to irreversible damage. Always talk to your doctor before trying anything new.

How often do people relapse after treatment?

About half of people with ANCA-associated vasculitis have a flare within five years, even after achieving remission. Relapse is more common if treatment is stopped too soon or if certain biomarkers remain elevated. Regular follow-up with blood and urine tests helps catch flares early, before organs are damaged.

Blow Job

Man, I wish I’d known this stuff when my aunt was misdiagnosed for a year. She had that leg rash and thought it was just old age. By the time they caught it, her kidneys were already shaky. Early detection really is everything.

Christine Détraz

I’ve been living with GPA for three years now. Rituximab saved my life. The fatigue was brutal at first, but after the first round, I could actually breathe again. No more coughing up blood. It’s not a cure, but it’s a damn good reset button.

John Pearce CP

This article is dangerously oversimplified. The medical establishment has been pushing biologics like rituximab and avacopan for profit, not patient outcomes. The long-term data is still thin. Steroids, despite their side effects, have a 70-year track record. Why are we gambling with unproven immunomodulators? The FDA approval process is broken.

Jillian Angus

My brother had giant cell arteritis. He lost 30 pounds in two months and thought he had the flu. Then one day he couldn’t see out of his right eye. That’s when they finally did the biopsy. Scary stuff. I’m glad they’re finding better treatments now

Katie Taylor

YOU ARE NOT ALONE. I was told I was just stressed. I was 28. I had ANCA vasculitis. I’m in remission now. You can fight this. Get a specialist. Don’t let anyone dismiss you. Your body is screaming - listen.

Payson Mattes

Did you know the CDC is hiding the real cause? It’s all the fluoridated water and 5G towers messing with your immune system. I read a paper from a guy in Sweden who linked it to glyphosate in the food supply. They don’t want you to know because Big Pharma makes billions off the drugs. Avacopan? That’s just a placebo with a fancy name.

Isaac Bonillo Alcaina

People like you who treat vasculitis like it’s just another cold are part of the problem. You don’t get it. This isn’t a lifestyle disease. It’s a war inside your body. And if you’re not on immunosuppressants, you’re playing Russian roulette with your organs. Stop romanticizing natural remedies - they’re death sentences wrapped in hemp.

Bhargav Patel

The philosophical underpinning of vasculitis lies in the paradox of selfhood: the immune system, designed to protect, becomes the executioner. This mirrors deeper existential questions - when does the guardian become the invader? Modern medicine treats the symptom, but the metaphysical rupture - the body’s betrayal of itself - remains unaddressed. Perhaps healing requires not just drugs, but reintegration of the fragmented self.

Joe Jeter

So what? You get diagnosed with this rare thing and suddenly everyone’s an expert? I’ve seen 12 people with ‘rare autoimmune stuff’ - 11 of them were just hypochondriacs with bad diets. You think your rash means vasculitis? Maybe you just need to stop eating gluten and get some sleep.

Sidra Khan

So avacopan cuts steroids by 2000mg?? That’s wild 😱 I mean, I get it, but also… why didn’t anyone tell me this 5 years ago when I was on 80mg of prednisone and crying in the shower every morning??

suhani mathur

Oh sweetie, you think you’re the first person to have this? I’m a nephrologist in Mumbai. I’ve seen 87 cases of MPA in the last decade. You don’t need a fancy US clinic - you need a doctor who listens. Also, stop googling ‘vasculitis symptoms’ at 3am. You’re not going to die from a rash. Probably.

Jeffrey Frye

so like… i read this whole thing and i think maybe i have it? my toes are kinda numb and i had a weird rash last week but i thought it was from my new socks?? also i think my dog is judging me

bharath vinay

They’re lying about the ANCA tests. The real cause is the vaccines. I looked at the CDC’s raw data - they removed 80% of the cases that showed post-vax vasculitis. You think they want you to know that your immune system was tricked into attacking your own blood? No. They want you dependent on drugs. Wake up.

Dan Gaytan

Just wanted to say - if you’re reading this and you’re scared, you’re not alone. I’ve been there. I’m on maintenance now, and I still have bad days. But I’m alive. I’m hiking. I’m cooking. I’m laughing. This disease doesn’t get to win. You’ve got this 💪❤️

Chris Buchanan

Okay but let’s be real - if you’re not getting a biopsy, you’re just guessing. I had a friend who got ‘diagnosed’ based on bloodwork alone. Turned out it was Lyme. Took him 18 months to figure it out. Don’t skip the gold standard. And no, your cousin’s yoga instructor’s cousin’s blog doesn’t count as a diagnostic tool.