When a generic drug hits the market, it’s not set in stone. Even small changes to how it’s made can trigger a full FDA re-evaluation - and that’s by design. The goal isn’t to slow things down. It’s to make sure every pill, capsule, or injection you take is just as safe and effective as the brand-name version, no matter who made it or where. But what exactly changes the game? And why do some manufacturing tweaks need months of FDA review while others don’t even require a notice?

What Counts as a Manufacturing Change?

Any tweak to the Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) side of a generic drug can be a trigger. That includes everything from switching suppliers for an active ingredient to upgrading a tablet press, changing the mixing time in a batch, or moving production from one factory to another. The FDA doesn’t care if the change seems minor - what matters is whether it could affect the drug’s identity, strength, purity, or quality.

For example, if a company switches from using a wet granulation process to a dry granulation process for a blood pressure pill, that’s a major change. The way the powder is compressed affects how fast the drug dissolves in your body. If it dissolves too slowly or too fast, it won’t work the same way. Even a 5% change in particle size of the active ingredient can require a full re-study.

According to FDA data from 2018 to 2022, manufacturing process changes made up nearly 16% of all post-approval submissions. Facility transfers were another big one - 24.5% of major change requests came from companies moving production lines. And it’s not just about location. Changing the type of equipment - say, from a batch mixer to a continuous mixer - can also force a full review, even if the final product looks identical.

The Three Tiers of FDA Review

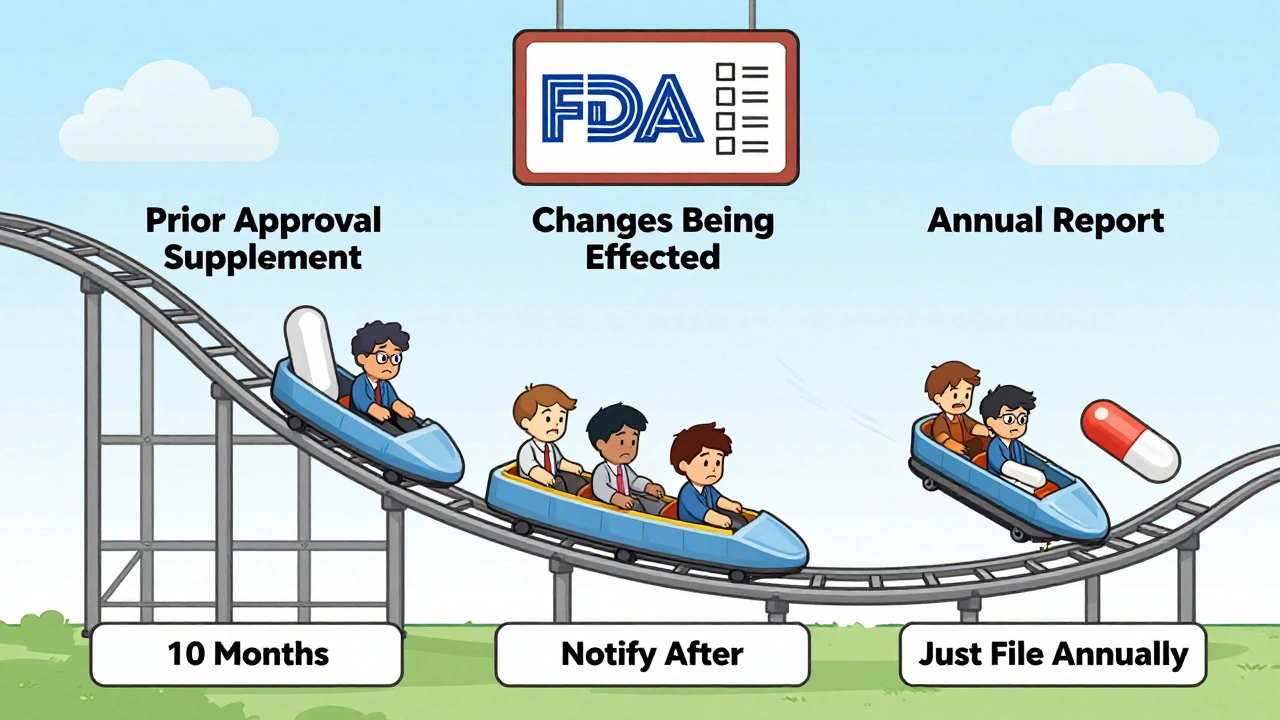

The FDA doesn’t treat every change the same. They’ve built a three-tier system to sort them by risk:

- Prior Approval Supplements (PAS) - These are the big ones. You can’t make the change until the FDA says yes. This applies to changes that could significantly affect safety or effectiveness. Think: new synthetic route for the active ingredient, major facility transfer, or switching to a new excipient that hasn’t been used before. The average review time? About 10 months. Some complex cases take over a year.

- Changes Being Effected (CBE) - These are medium-risk changes. You can make the change right away, but you have to tell the FDA within 30 days (CBE-30) or immediately (CBE-0). This includes things like minor adjustments to specifications, updated stability testing protocols, or changing the packaging material. The FDA reviews these after the fact.

- Annual Reports (AR) - The lowest risk. These are tiny tweaks - like changing the font on the label or updating a manufacturing record format. You just list them in your yearly report. No prior notice needed.

Here’s the catch: figuring out which category your change falls into isn’t always clear. A 2023 survey of 127 generic manufacturers found that 78.4% struggled with this. One company upgraded a tablet press to reduce breakage - same output, same quality. But because the machine had a different compression force profile, the FDA classified it as a PAS. It took 18 months to approve.

Why Some Changes Trigger Full Re-Evaluation

The FDA’s main rule: the generic must be bioequivalent to the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). That means it must deliver the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same rate. If a manufacturing change could alter that - even slightly - the FDA requires proof.

For simple generics like metformin or lisinopril, this is usually straightforward. But for complex drugs - think inhalers, injectables, or peptide-based treatments - even tiny changes can have big effects. In 2021, the FDA clarified that any new impurity in a peptide drug must be under 0.5%, and the manufacturer must prove it doesn’t harm patients. That’s not just paperwork - it requires new analytical methods, stability studies, and sometimes clinical data.

And it’s not just about the drug itself. If you change the manufacturing site, the FDA will inspect it. If the new facility hasn’t been inspected before, or if it’s in a country with a history of compliance issues, that can add 6-9 months to the timeline. One company moved production from India to the U.S. for a generic asthma inhaler. The change improved supply reliability, but the FDA inspection took 11 months. They had to revalidate every step of the process - from raw material handling to final packaging.

The Cost of Change

There’s a hidden price tag here. The average cost of a PAS submission is around $287,500, according to 2023 industry data. That’s not just filing fees. It’s months of internal work: validating processes, running stability studies, writing reports, hiring consultants, preparing for inspections. For a low-margin generic drug selling for pennies per pill, that’s a huge investment.

That’s why many companies avoid making improvements - even if they’d make the product better. One quality manager on Reddit shared how their company skipped a cleaner, more efficient mixer because the FDA review would’ve delayed production for over a year. The old machine broke down more often, but the regulatory risk wasn’t worth it.

But it’s not all bad. Companies using Quality by Design (QbD) principles - building flexibility into the process from day one - report 40% fewer PAS submissions. Teva, for example, used continuous manufacturing for amlodipine and cut their PAS review time from the usual 14 months to just 8. How? They mapped out the entire process during development, identified the critical parameters, and proved to the FDA that small variations wouldn’t affect quality. That’s the smart way to do it.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The FDA is trying to fix the system. In September 2023, they launched the ANDA Prioritization Pilot Program. If you make your drug - including the active ingredient - in the U.S., and run your bioequivalence studies here too, you can get your PAS reviewed in 8 months instead of 10-14. That’s a game-changer. The agency estimates this could drive $4.2 billion in new U.S. manufacturing investment by 2027.

Then there’s the PreCheck program, announced in February 2024. It’s a two-step inspection process for high-priority facilities. Instead of waiting for a full inspection after submitting a PAS, you can get your facility pre-approved before you even file. That could cut facility transfer timelines in half - from 18 months to 9.

And in early 2024, the FDA released draft guidance for complex generics. It proposes a new tiered risk system that could reduce PAS submissions by up to 35% for minor changes. If finalized, this would be the biggest shift since GDUFA in 2012.

What Manufacturers Need to Do Now

If you’re a generic manufacturer, here’s what works:

- Build flexibility into your ANDA from the start. Use QbD. Define your design space. Know which parameters matter and which can wiggle without risk.

- Use Process Analytical Technology (PAT). Real-time monitoring of your process reduces surprises. Companies using PAT saw 32.6% fewer PAS submissions over five years.

- Don’t wait until you have a problem to talk to the FDA. Schedule pre-submission meetings early. The FDA’s own data shows that companies that did this had 31.4% faster approval times.

- Consider U.S. manufacturing. The prioritization program is real. If you can make your drug here, you’ll get faster reviews - and you’ll be less vulnerable to global supply chain shocks.

It’s not about avoiding change. It’s about managing it smartly. The best generic manufacturers aren’t the ones who make the fewest changes - they’re the ones who make the right changes, with the right data, at the right time.

What Happens If You Change Something Without Approval?

Skipping the process is risky. If the FDA finds out you made a PAS-level change without approval, they can:

- Block your product from being sold

- Issue a warning letter

- Require a recall

- Delay future applications

One company in 2022 switched to a cheaper excipient without telling the FDA. The drug passed all internal tests. But during a routine inspection, the FDA noticed the change. The product was pulled from shelves. The company lost $17 million in sales and had to re-submit a PAS. It took 15 months to get back on the market.

There’s no shortcut. The system is slow, expensive, and sometimes confusing - but it exists to protect you.

What manufacturing changes require an FDA Prior Approval Supplement (PAS)?

Any change that could affect the safety, effectiveness, or quality of a generic drug requires a PAS. This includes switching to a new synthetic route for the active ingredient, moving production to a new facility, changing the manufacturing process in a way that alters drug release (like granulation method), or introducing a new excipient not previously approved. The FDA requires full chemistry, manufacturing, and bioequivalence data before approving these changes.

Can I make a manufacturing change and notify the FDA later?

Yes - but only for certain changes classified as Changes Being Effected (CBE). These include minor updates to specifications, stability protocols, or packaging materials. You can implement the change immediately, but you must notify the FDA within 30 days (CBE-30) or immediately (CBE-0). You cannot use this route for changes that impact bioequivalence or drug release. If you’re unsure, consult FDA guidance or request a pre-submission meeting.

Why does the FDA take so long to approve manufacturing changes?

The FDA reviews PAS submissions to ensure the generic drug remains bioequivalent to the brand-name version. This requires evaluating analytical data, stability studies, process validation, and sometimes new bioequivalence trials. Complex changes - like facility transfers or new manufacturing technologies - can take 10-14 months because they involve multiple departments and may require inspections. The average review time is 10 months, but delays happen when submissions are incomplete or require additional data.

How can manufacturers reduce the time and cost of FDA re-evaluation?

Use Quality by Design (QbD) during initial development to build flexibility into the manufacturing process. Implement Process Analytical Technology (PAT) for real-time monitoring. Schedule pre-submission meetings with the FDA early. Consider U.S.-based manufacturing to qualify for the ANDA Prioritization Pilot Program, which can cut review times to 8 months. Companies with mature quality systems have seen approval timelines drop by over 30%.

Are there any new FDA programs to speed up generic manufacturing changes?

Yes. The ANDA Prioritization Pilot Program, launched in September 2023, accelerates review for generics made entirely in the U.S. - including the active ingredient and finished product. The PreCheck program, introduced in February 2024, allows facilities to get pre-approved before submitting a change, cutting inspection times in half. Draft guidance released in January 2024 also proposes a tiered risk system that could reduce PAS submissions for minor changes by up to 35%.

Manufacturing a generic drug isn’t just copying a pill. It’s a science. And the rules exist to make sure that copy works exactly like the original - every time, for every patient. The system isn’t perfect, but it’s getting smarter. The companies that thrive won’t be the ones avoiding change. They’ll be the ones who understand it, plan for it, and use it to build better medicines.

Ruth Witte

This is such a dope breakdown! 🙌 I work in pharma QA and honestly? The PAS system is a nightmare... but I get why it exists. One tiny switch in excipient and boom - 14 months gone. 😩

Noah Raines

The FDA's just being extra. If the pill looks the same and works the same, why do we need a year-long audit? 🤷♂️ We're not launching a rocket here.

Gilbert Lacasandile

I think the system is actually pretty smart. I used to work at a generic maker that cut corners - ended up with a recall. Lost $20M. Never again. Better safe than sorry.

Lola Bchoudi

QbD + PAT is the only way forward. If you're not leveraging design space and real-time process analytics, you're operating in the stone age. The data's there - stop treating compliance like a checkbox. It's a strategic advantage.

Morgan Tait

You know who really benefits from all this? Big Pharma. They use the FDA’s bureaucracy to block generics. The ‘bioequivalence’ standard? Made up. The real drug is the placebo in the bottle - and they’re all in on it. 🕵️♂️💊

Christian Landry

honestly tho why does it take so long? like i get safety but its just a pill right? i mean i got my generic adderall and it works fine. why the 10 month wait? 🤔

Katie Harrison

I appreciate the nuance here. In Canada, we have Health Canada’s equivalent - and it’s just as opaque. But I’ve seen patients suffer when supply chains break. This isn’t red tape. It’s lifelines.

Michael Robinson

It’s not about the pill. It’s about trust. If we can’t trust that the same pill works the same way every time - then what do we trust?

Kathy Haverly

Oh please. The FDA is just a tool for corporate monopolies. They’re not protecting you - they’re protecting profits. That $287k fee? That’s a tax on small companies so big pharma can keep their price gouging.

Andrea Petrov

I’ve read the leaked emails. The FDA has a secret list of ‘approved’ suppliers. If you’re not on it? You’re out. It’s not about safety - it’s about who you know. The whole system is rigged.

Haley P Law

I JUST GOT MY GENERIC LIPITOR AND IT MADE ME SICK. LIKE, REALLY SICK. IS THIS WHY?? I'M SENDING THIS TO THE FDA RIGHT NOW. 🚨

Andrea DeWinter

For anyone new to this: start with the FDA’s CMC guidance documents. They’re free. Read the 2023 draft on complex generics. It’s a game-changer. And if you’re a small biz - use the pre-submission meetings. They literally save months.

Steve Sullivan

the real question is... why do we let corporations decide what’s safe? the system’s broken. not because it’s too strict - because it’s too tied to money. if the FDA was run by doctors and patients, not consultants and lawyers... we’d be fine.

George Taylor

So... let me get this straight. You’re telling me a company spent $287,500 and 18 months to switch from a mixer that breaks every 3 weeks to one that doesn’t... and they’re still not allowed to sell the product? This isn’t regulation. It’s institutionalized cruelty.